Some Coffee With Your Tea?

You pour some coffee into your tea, and then pour some of that back into your coffee. Is there more coffee in your tea or more tea in your coffee?

Welcome to Fiddler on the Proof, the spiritual successor to FiveThirtyEight’s The Riddler column.

Every Friday morning, I present mathematical puzzles intended to challenge and delight you. Most can be solved with careful thought, pencil and paper, and the aid of a calculator. The “Extra Credit” is where the analysis typically gets hairy, or where you might turn to a computer for assistance.

I’ll also give a shoutout to 🎻 one lucky winner 🎻 of the previous week’s puzzle, chosen randomly from among those who submit their solution before 11:59 p.m. the Monday after puzzles are released. I’ll do my best to read through all the submissions and give additional shoutouts to creative approaches or awesome visualizations, the latter of which could receive 🎬 Best Picture Awards 🎬.

This Week’s Fiddler

This week’s puzzle was related to me by Jay Goldman:

I have two glasses, one containing precisely 12 fluid ounces of coffee, the other containing precisely 12 fluid ounces of tea.

I pour one fluid ounce from the coffee cup into the tea cup, and then thoroughly mix the contents. I then pour one fluid ounce from the (mostly) tea cup back into the coffee cup, and then thoroughly mix the contents.

Is there more coffee in the tea cup, or more tea in the coffee cup?

This Week’s Extra Credit

I have two glasses that can hold a maximum volume of 24 fluid ounces. Initially, one glass contains precisely 12 fluid ounces of coffee, while the other contains precisely 12 fluid ounces of tea.

Your goal is to dilute the amount of coffee in the “coffee cup” by performing the following steps:

Pour some volume of tea into the coffee cup.

Thoroughly mix the contents.

Pour that same volume out of the coffee cup (i.e., into the sink), so that precisely 12 fluid ounces of liquid remain.

After doing this as many times as you like, in the end, you will have 12 ounces of liquid in the coffee cup, some of which is coffee and some of which is tea. In fluid ounces, what is the least amount of coffee you can have in this cup?

Making the ⌊Rounds⌉

There’s so much more puzzling goodness out there, I’d be remiss if I didn’t share some of it here. This week, I’m sharing the last puzzle of 2025 from X’s Puzzle Corner, which asks for the probability that one box (each of whose dimensions are randomly chosen between zero and some maximum value) will fit inside another box with similarly, but independently, randomized dimensions.

If you have time, check out the (as yet unsolved?) extra credit, where boxes can be tilted inside each other. (That was my initial interpretation of the original puzzle.)

Want to Submit a Puzzle Idea?

Then do it! Your puzzle could be the highlight of everyone’s weekend. If you have a puzzle idea, shoot me an email. I love it when ideas also come with solutions, but that’s not a requirement.

Standings

I’m tracking submissions from paid subscribers and compiling a leaderboard, which I’ll reset every quarter. All timely correct solutions to Fiddlers and Extra Credits are worth 1 point each.

The results from Q4 are in, and the finest of Fiddlers, who each solved all 24 puzzles, are:

👑 Connor Colombe 👑 from Austin, Texas

👑 Ed Foley 👑 from Redmond, Washington

👑 Eric Widdison 👑 from Kaysville, Utah

👑 Josh Arnold 👑 from Arlington, Massachusetts

👑 Michael Schubmehl 👑 from Hinsdale, Illinois

👑 Peter Exterkate 👑 from Sydney, Australia

👑 Peter Ji 👑 from Madison, Wisconsin

Congratulations to all who participated; the final standings are below. (If you think you see a mistake in the standings, kindly let me know.) And special congrats to Michael Schubmehl, who correctly answered all 100 puzzles in calendar year 2025!

While ChatGPT-5 Reasoning did very well, correctly solving 21 of the 24 puzzles on its first attempt, it clearly didn’t get everything right. In Q1, we’ll see how the latest AI models perform.

I will be reaching out to the first-time top finishers so I can send along a fancy-schmancy t-shirt prize! Also, this week’s puzzles mark the beginning of the next quarter (Q1). If you’d like your shot at glory (and a t-shirt), become a paid subscriber today!

Last Week’s Fiddler

Congratulations to the (randomly selected) winner from last week: 🎻 Aaron Slepkov 🎻 from Peterborough, Ontario. I received 24 timely submissions, of which 19 were correct—good for a 79 percent solve rate.

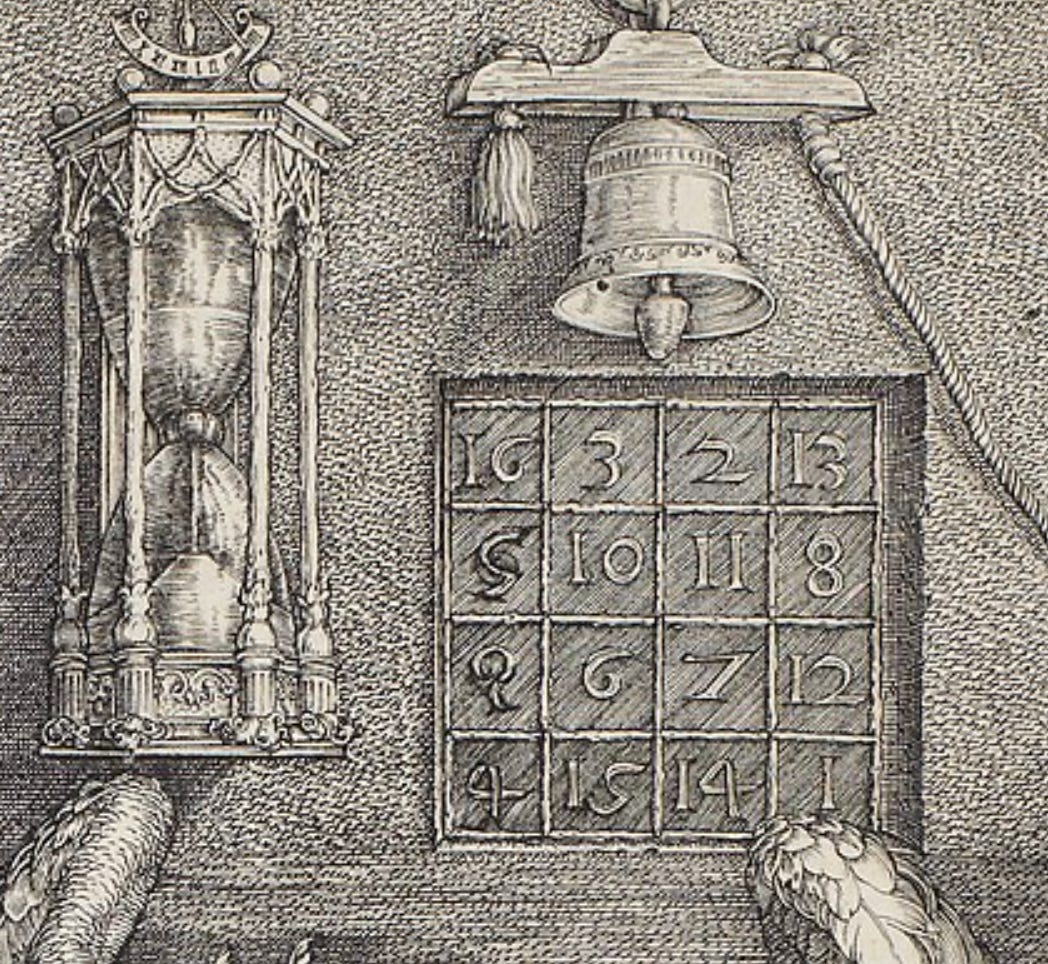

A magic square is a square array of distinct natural numbers, where each row, each column, and both long diagonals sum to the same “magic number.” A particularly famous example of a four-by-four magic square with a magic number of 34 appears in Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 (note the adjacent numbers 15 and 14!) etching, Melencolia I:

A prime magic square is a magic square consisting of only prime numbers. Last week, you were asked to construct a four-by-four prime magic square with a magic number of 2026—if that was even possible!

To have any four distinct prime numbers sum to 2026—an even number—all four of them had to be odd. In other words, 2 couldn’t be one of the four. Meanwhile, their average had to be 506.5, so we were dealing with some pretty sizable numbers here.

Furthermore, 2026 has a remainder of 2 when divided by 4, whereas odd numbers have remainders of 1 or 3 when divided by 4. For the sum of four odd numbers to have a remainder of 2, you needed either (a) three numbers to have a remainder of 1, while the fourth had a remainder of 3, or (b) three numbers to have a remainder of 3, while the fourth had a remainder of 1.

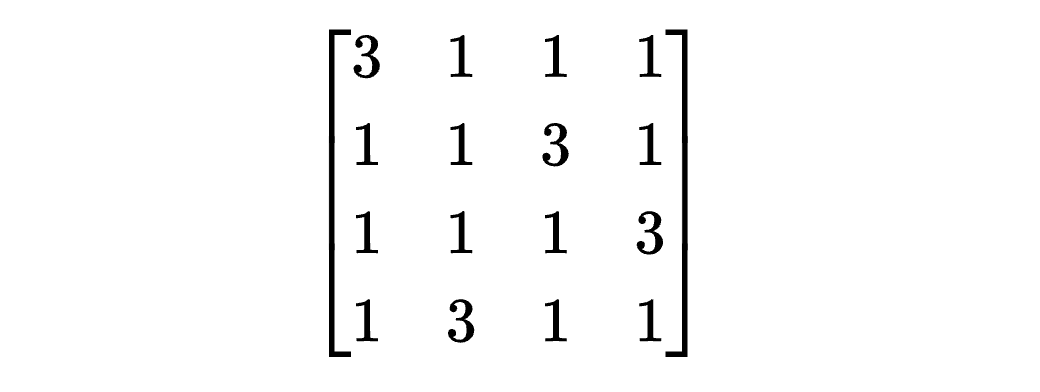

There were a few different ways to organize 16 odd numbers into a four-by-four grid so that each row, column, and diagonal had either exactly one or three numbers with a remainder of 1. Here was one such way (“1” represents a remainder of 1, “3” represents a remainder of 3):

That said, there are 305 odd prime numbers less than 2026, 148 of which have a remainder of 1 and 157 of which have a remainder of 3. There were still so many cases to check!

Another approach was to first work out—with some computer assistance, perhaps—all the ways you could have four primes sum to 2026. Two such quadruples were (3, 5, 7, 2011) and (3, 5, 19, 1999), but there were many, many more—solver Jason Weisman found 90,175 such quadruples. In theory, once you had a partial or complete list, you could then identify four mutually exclusive quadruples (for the four rows in the magic square, say) such that the columns and diagonals also summed to 2026.

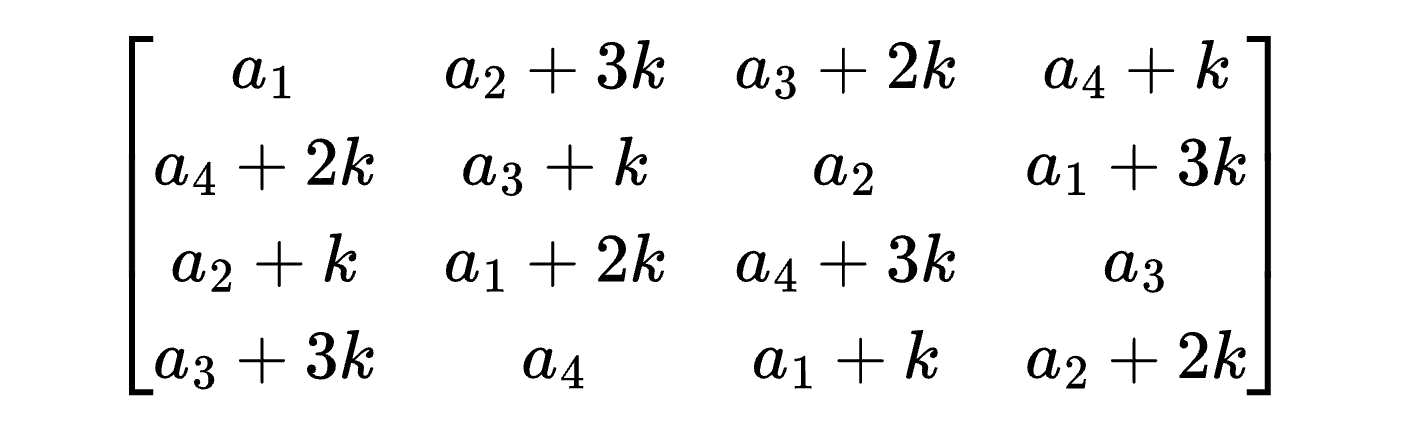

Other solvers instead turned to specialized techniques that were guaranteed to produce a magic square, and then tweaked the numbers so that they were all prime. For example, solver Q P Liu used Ramanujan’s magic square:

Note that this square consisted of four arithmetic sequences that each started with a different value (a1, a2, a3, and a4) and had the same common difference k. These sequences were arranged in such a way so that the sum of each row, column, and diagonal was a1 + a2 + a3 + a4 + 6k.

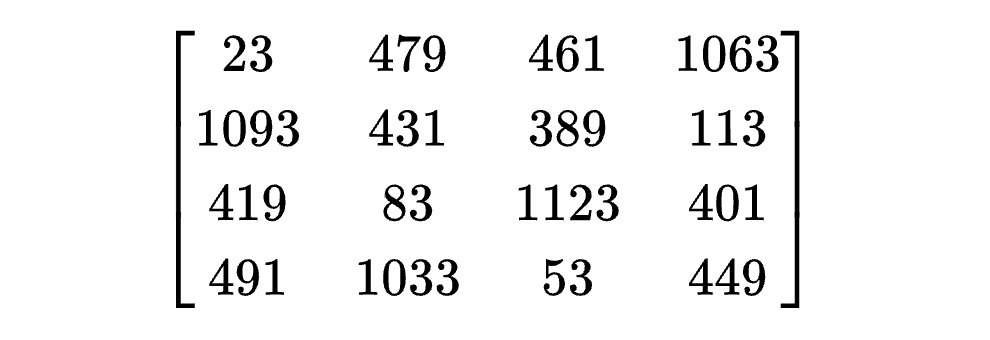

From there, you could pick a value of k that was a frequent common difference among arithmetic sequences of primes. For example, if k was 30, then you needed a1 + a2 + a3 + a4 + 6·30 = 2026, or a1 + a2 + a3 + a4 = 1846. Four such primes that fit the bill were 23, 389, 401, and 1033. Their sum was indeed 1846, and if you added 30 to each of them a few times, you got the following arithmetic sequences of primes:

23, 53, 83, 113

389, 419, 449, 479

401, 431, 461, 491

1033, 1063, 1093, 1123

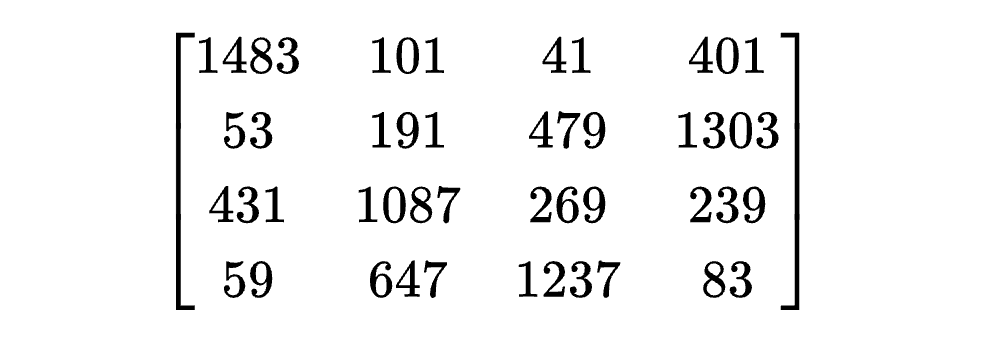

Positioning these primes in Ramanujan’s magic square gave you:

If you looked at the remainders of all these primes after dividing by four, you found a pattern of 1s and 3s similar to the one we found earlier.

Q P Liu found 69 of these Ramanujan-style prime magic squares, but there were many others, such as this one from solver David Kong:

As for ChatGPT … it threw an OEIS sequence at me containing magic numbers for four-by-four prime magic squares—a sequence that has been hypothesized to include every even number greater than 152. But that’s as far as it went, which meant no credit for the LLM.

Last Week’s Extra Credit

Congratulations to the (randomly selected) winner from last week: 🎻 Tom Keith 🎻 from Toronto, Canada. I received 16 timely submissions, of which 10 were correct—good for a 62.5 percent solve rate.

For Extra Credit, you were asked to find all values of N for which it was possible to construct an N-by-N prime magic square with a magic number of 2026. (Remember, the numbers in a magic square all had to be distinct!)